River Wars, Barony of Iron Bog

Awarded September 7, AS 48 (XLVIII)

My very first Peerage piece.

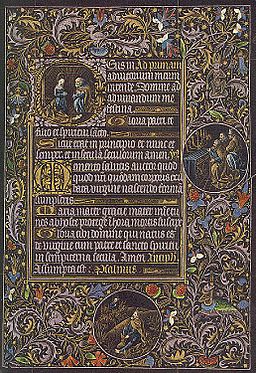

At some point after Diego received his Writ, Alys had him look through examples of manuscripts to get a feel for what he might like and of course he fell in love with the Sforza Black Hours she had received when she was made a Tyger of the East. Black Hours he would like, Black Hours he would get.

I've never attempted this style before, however Nataliia had just completed one. We managed to find time to sit down at Pennsic for a couple of hours so that I could pick her brain and play with the materials she had used. It was useful, and she was able to confirm many of the assumptions I'd initially had upon receipt of the assignment. To say I was intimidated is a major understatement.

|

| Ms 1856, f.61 |

All of the Black Hours I've looked at appear to be written in silver with one set of notable exceptions, those contained in the Mira Calligraphiae Monumenta [1] housed in the Getty collection. These pages are usually folios of parchment dyed black during the stretching and scraping process.

Since real silver is likely to tarnish [2] I'm using my W&N silver gouache. The calligraphy is done in this same gouache, watered down so that it flows easily from the nib (Mitchell #5). Writing silver on the black paper wasn't as difficult as I had imagined it would be, although it did take almost twice as long as writing in regular ink. The biggest issue was that I needed to continually mix the gouache [3] and clean my nib every few words so that I could keep a fairly consistent and sharp line for the writing. I also had to use a larger nib than I had wanted since I just couldn't achieve crisp lines with my usual #6 nib. As a by-product the entire piece is larger than I had originally wanted it to be.

This project requires A LOT of gold. The few images I have available to me for the Sforza Hours suggest that most of the gold appears to be painted rather than gilded. For the guide-lines and the written gold words I used my Holbein gold gouache since it works in the same fashion as the silver and was just easier. However for the rest of this piece I wanted a more dramatic luminescence than the gouache offers, so I made my own powdered gold out of the 23k sheets I use for gilding (keep an eye out for a follow up instruction post for this!).

|

| Ms 1856, f.32 verso |

Just when I was completely sick of working in white I was finally able to switch to the 23k powdered gold I had created specifically for this piece. To accompany my dish of prepared gold pigment, I also have a small dedicated jar which contains distilled water to collect any scraps from my dedicated gold paintbrush. By doing this I'm always cleaning the dedicated brush in clean water and retaining any fragments during the process, these can then again be prepared for use as gold pigment at a later date.

The gold work actually became as annoying as the white work due to the length of time it ended up taking. It didn't go on nearly as smoothly as I hoped that it would, even though my paint was "wet". In hindsight I wonder if it needed he gold grains to be finer by more grinding.

The silver within the borders was done concurrently with the gold so that I would keep the flow looking consistent.

Next came the colours, all of which went on smoothly and easily. In testing I found that my Cadmium Red gave a much nicer colour than the Spectrum Red that I tend to use more often. My guess is that because the Cadmium Red leans towards orange/yellow it played well against the substantial amount of gold. The Ultramarine blue was cut with a little Permanent White as Nataliia had suggested during out time at Pennsic, it makes for a more vibrant colour than the base tube-colour.

Diego has served over many years in three separate Kingdoms which I was asked to represent on this piece, the roundels within the borders made an ideal location for these; from left to right - Ansteorra, Aethelmearc, and the East. The fourth is Sharc, an East Kingdom household of which Diego is a member. His arms are displayed in the decorated initial D.

Details:

Details:Calligraphy & Illumination by Isabel Chamberlaine.

Inspired by the Black Hours of Galeazzo Maria Sforza as seen to the right.

Paper: Black 120gsm paper (I forget which brand).

Materials: Holbein "Pearl Gold" and Windsor & Newton "Silver" gouaches for layout lines, calligraphy, and select details. 23k powdered gold in a gum arabic binder for the majority of gold-work. Various W&N gouache for any of the coloured areas.

Text by Alys Mackyntoich

We, Gregor, by right of arms King of the East, and Kiena, his Queen, considering the great, long and earnest travails and labours sustained by Diego Miguel Munoz de Castilla in the service of the art of defence and the safe practices of same for some score of years and more, and after due consideration of the cause above-written and other good and thankful service done by the said Diego to our sister realms of Aethelmearc and Ansteorra, do therefore ordain, approve and confirm the elevation of the said Diego to the Order of the Pelican, and do convey therewith all liberties and privileges attendant thereupon. And we do further by these our present letters give, grant and convey to the said Diego the right to bear arms by letters patent in the following form: Argent, on a bend sable three escallops palewise argent. And we do further ratify and approve, for ourselves and our successors, that the gifts and grants made herein shall be in all time coming effectual, good, valid and sufficient perpetually in all and sundry points, and do hereby ordain the same to be put to due execution, and to have full force, strength and effect in all time coming. Given at Iron Bog upon 7 September in the forty-eight year of the Society.

Footnotes:

[1] This was confirmed during a class I happened to take at Pennsic 2013 that presented findings by the Getty that the black hours contained within the Mira Calligraphiae Monumenta were actually created using a resist technique. Although I need to track down the original source from the Getty, the gist of it was that the calligraphy was written with some sort of resist on white paper, it was then washed over in black ink to create the dark page. The resist is then rubbed away to reveal the calligraphy as the white of the page.

[2] I really do need to test out the tarnishing of real silver on the work we do in the SCA. Just how long does silver-leaf take to tarnish?

[3] Both silver and gold gouache need to be regularly mixed since the metallic pigment has a tendency to settle.

Scroll ID: Isabel C XLII

Completed Sept. 5, 2013